Question 5#

A 96-year-old female is admitted to the intensive care unit for closer hemodynamic monitoring following uncomplicated deployment of a drug-eluting stent to the first obtuse marginal, via the left radial artery, in the context of a presentation consistent with an ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Four hours postprocedure, the patient develops acute hypotension necessitating vasopressor support.

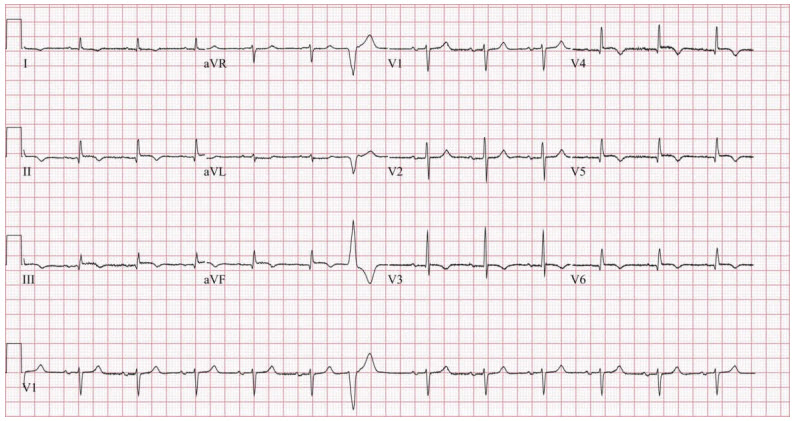

A 12-lead electrocardiogram is performed.

Compared to her postintervention electrocardiogram, ST segment elevations in leads II, III, aVF, V5, and V6 persist but are less prominent. Otherwise, there are no significant changes. Assessment of her left radial access site is unrevealing.

What is the best next step in management?

A. Repeat diagnostic coronary angiographyB. Urgent surface echocardiogram

C. Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen

D. Right heart catheterization

Correct Answer is B

Comment:

Correct Answer: B

Complications of diagnostic coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention that can cause hypotension include coronary perforation leading to cardiac tamponade, access site complications leading to bleeding, or intracoronary artery complications (dissection, stent thrombosis, stent migration) leading to left ventricular dysfunction and impaired cardiac output. In the absence of a clinical syndrome or electrocardiographic evidence of stent compromise, attention should be directed toward the access site which, particularly with radial access, can be visually inspected. In the absence of access site compromise, transthoracic echocardiography should be considered for evaluation of pericardial effusion and mechanical complications of myocardial infarction.

Coronary artery perforation is a rare complication occurring in less than 1% of treated lesions. Perforation can be caused by a wire exiting a vessel or by compromise of the vessel wall by a balloon, stent, or other intracoronary devices. Most cases of perforation are identified intraprocedurally but upward of 13% of cardiac tamponade instances can be delayed and occur within 24 hours after departure from the catheterization laboratory. Intraprocedural perforations can be managed with balloon occlusion of the perforated artery. If tamponade were to develop, emergent pericardiocentesis should be pursued. For delayed presentations, repeat angiography can be considered to identify active extravasation that may benefit from a trial of balloon occlusion or coil embolization.

References:

- Stankovic G, Orlic D, Corvaja N, et al. Incidence, predictors, in-hospital, and late outcomes of coronary artery perforations. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):213-216.

- Ellis SG, Ajluni S, Arnold AZ, et al. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90(6):2725-2730.